Data and Proposals for Equality 2024

Inequality between men and women is present in various aspects of life, from the home to the labor market. Women are underrepresented in the global labor market, and no country has achieved gender equality in workplaces. Mexico is the fourth country with the lowest economic participation of women in Latin America. Promoting the inclusion of more women in the labor market and improving their conditions to support their professional growth not only benefits half of the population but also their families, and it is strategically important for enhancing the country's competitiveness.

In the context of International Women's Day, the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness (IMCO), in collaboration with the National Institute for Women (INMUJERES) and UN Women Mexico, analyzed a series of gender indicators within households and the labor market, focusing on leadership positions in both the private and public sectors.

This document presents evidence-based proposals to boost women's economic participation. In Mexico’s current electoral context, these proposals can enrich the agendas of federal and local candidates.

Gender gaps at home

Women primarily perform household and caregiving tasks, crucial for the everyday maintenance and well-being of families and individuals and society in general. Despite this, they do not receive any compensation in return. While, on average, men dedicate 16 hours a week to unpaid household and caregiving work, women dedicate 40 hours. Furthermore, 17.2 million women exclusively engage in household tasks, in contrast to 992 thousand men who exclusively perform these tasks. In other words, there are 17 times more women than men in this situation.

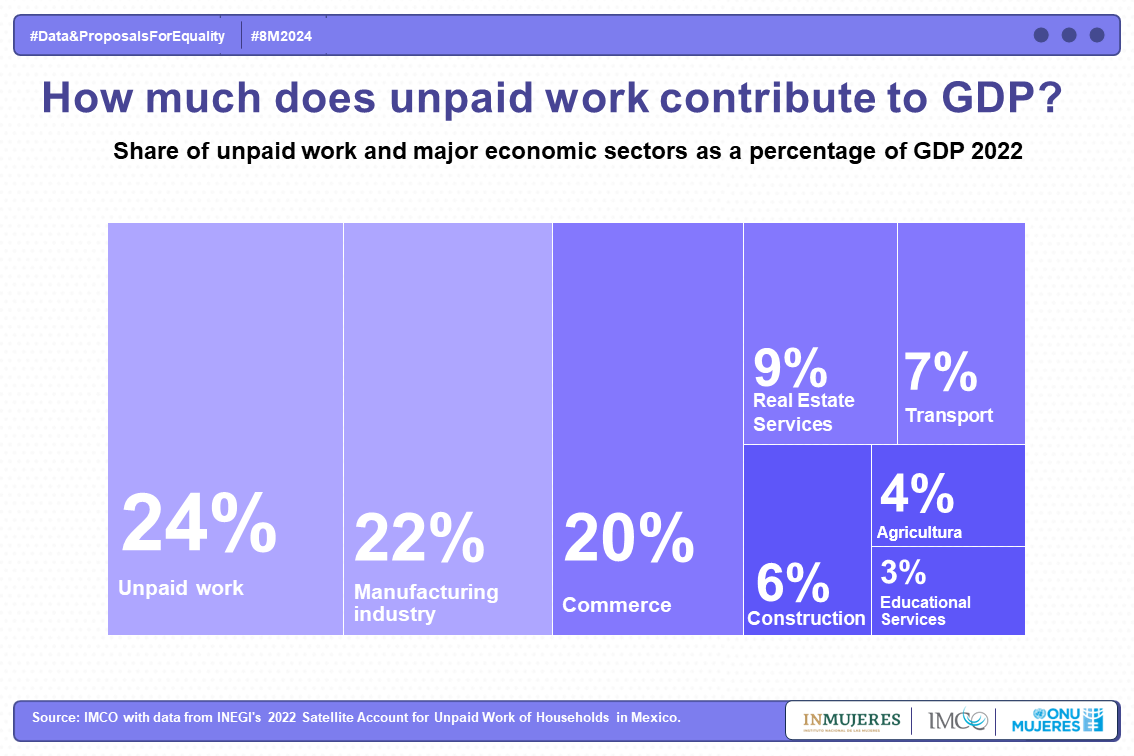

Beyond caregiving work, women also spend more time on other essential tasks to support their household and its members, such as cleaning, shopping, or cooking. It is estimated by INEGI that unpaid work has an economic value of 7.2 trillion pesos in Mexico. If unpaid work were an industry, it would account for 24% of the national Gross Domestic Product (GDP), a figure higher than the value of economic sectors such as manufacturing (22%) or trade (22%).

If the value of household and caregiving tasks is added, women contribute 2.6 times more economic value than men through unpaid work. This unequal distribution limits the time available for women to invest in their personal development and professional growth. According to INEGI, nine out of 10 people who leave the labor market to perform caregiving tasks are women.

Gender gaps in the labor market

In Mexico, women's participation in paid employment stands at 46%, while men's participation is 77%, according to the National Occupation and Employment Survey (ENOE). Furthermore, there has been minimal change in women’s participation in the labor market over the past two decades. Between 2005 and 2023, participation increased by five percentage points, rising from 41% to 46% during this period. At this rate, it would take 119 years for women to reach the economic participation rate of men.

Women participating in the labor market tend to face unfavorable working conditions, including:

- High rates of informality: 55% of women are employed in informal conditions compared to 49% of men in the same situation. This means that more than half of female workers in the country lack legal certainty, have no access to health services, and do not receive employment benefits. Put simply, the availability of health services and social protection depends on whether they are employed in formal jobs. Informality also implies that women in this situation earn, on average, 48% less than their female counterparts in formal jobs.

- Gender income gap: On average, women earn $6,360 pesos per month (~380 USD), while men earn $9,762 pesos (~580 USD). This results in an income gap of 35%, according to INEGI. In other words, for every 100 pesos a man earns, a woman receives $65 pesos.

- Workplace violence: Three out of 10 women have experienced workplace violence throughout their lives. The most frequently reported type of violence by women is gender-based discrimination, reflected in situations such as having fewer promotion opportunities or receiving lower pay than men. 24% of female workers aged 25 to 34 reported experiencing such situations. However, only 8% of women sought support or reported the discrimination they faced. The main reason for not doing so was considering it is unimportant (32%), followed by fear of consequences or threats (22%).

These gaps within the labor market result in lower economic autonomy for women. In Mexico, 25% of women do not have their own income. Additionally, women rely more on economic transfers from third parties, such as government programs, remittances, or family transfers, in comparison to men. Specifically, 54% of women’s income comes from third-party sources, while for men, this proportion decreases to 31%. This implies that women have less economic independence, which can limit their autonomy in decision-making.

Gender gaps in leadership positions

Without overlooking a series of structural factors such as widespread violence, cultural practices, or gender stereotypes, gender inequalities faced by women at home due to a higher burden of unpaid care work and unfavorable conditions within the labor market also result in a low presence of women in leadership positions, both in the private and public sectors.

Within companies. Women's talent is lost as they climb the corporate ladder. According to a study conducted by IMCO in collaboration with Kiik Consultores, although women make up 43% of the workforce in nearly 200 analyzed companies, the proportion decreases as the hierarchical level increases.

- Women hold 25% of legal department leadership positions, 11% of CFO positions, and only 4% are in CEO positions.

- The presence of women on corporate boards in Mexico is 13%, which is 17 percentage points below the global average.

- If the current trend continues, the country will achieve gender parity on corporate boards by 2052.

Within the public sector. Although gender quotas have accelerated the entry of more women into political positions, the landscape of the public sector reflects certain similarities with the private sector.

- Mexico is the third country in Latin America with the lowest presence of women in top-level hierarchical positions in the public sector.

- Within Ministries at the federal level, women hold 47% of liaison positions, the lowest hierarchical level. However, this proportion decreases to 33% in higher-level leadership positions (undersecretaries, unit heads, and general directors).

- This low representation of women translates, at an aggregate level, into lower incomes for women working in Ministries. The gender income gap in leadership positions is 11%, meaning that for every 100 pesos a man earns, a woman earns 89 pesos in leadership positions within the secretariats.

Proposals towards gender equality

In a context where gender stereotypes persist and women predominantly assume caregiving roles, coupled with the inflexibility of the labor market, the progression of women into higher-ranking positions is further constrained by the demands of motherhood and responsibilities for other family members. According to a survey by IMCO on professional growth with a gender perspective, 51% of mothers reported having paused their professional careers for personal reasons, compared to 20% of fathers.

In this regard, a recently published article in The Economist addresses how the "motherhood penalty" impacts the quality and possibility of women's employment after the birth of their first child and during the first decade after childbirth. Although such a decline is a global trend, in the Mexican context, the impact of motherhood on employment does not show significant recovery in the first ten years, unlike in other countries.

The decision to interrupt professional careers is often not merely a personal one but is frequently motivated by the absence of inclusive policies and alternative care options. Therefore, it is crucial for both the private and public sectors to invest and collaborate in an intersectoral manner to establish conducive conditions that enable women to grow professionally

In line with the theme "Invest in women: Accelerate progress” set by UN Women globally for International Women's Day 2024, IMCO, INMUJERES, and UN Women Mexico propose:

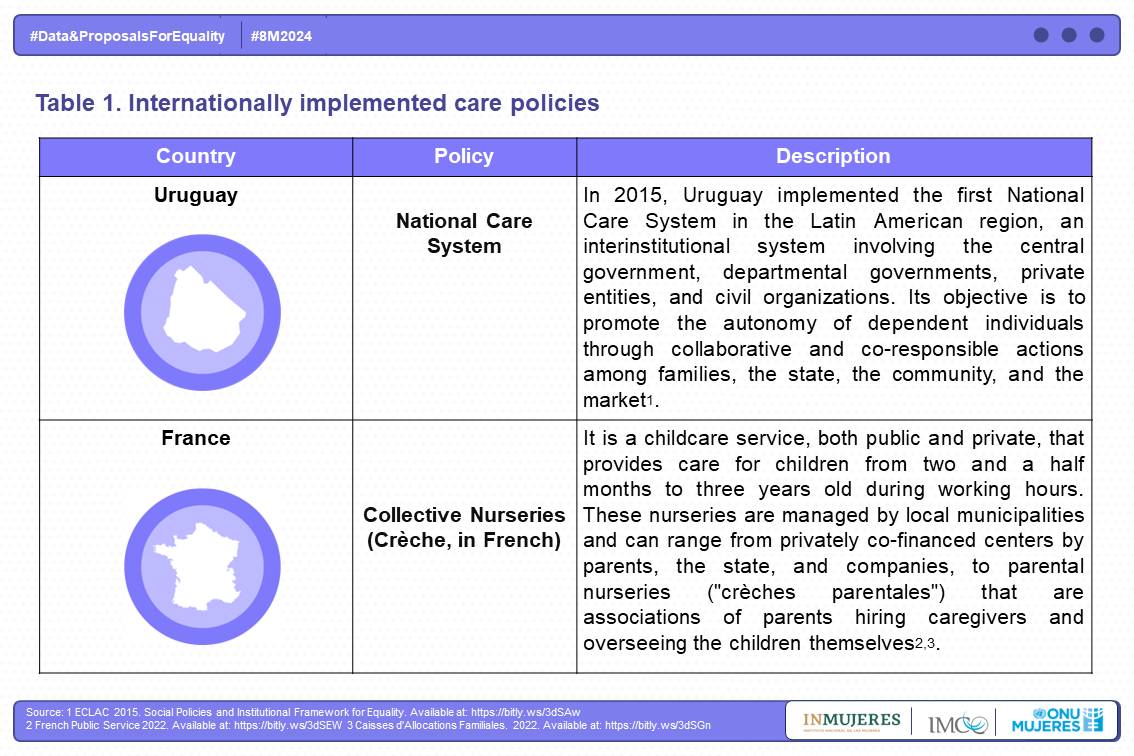

- Redistribute caregiving responsibilities and invest in them. To establish a National Care System, which is a coordination system among public institutions addressing the country's care needs. The Ministry of Finance estimates that an annual public investment equivalent to around 1.4% of the national GDP would be required, which could be financed through a tripartite system involving the State, businesses, and employees.

To achieve this, a constitutional reform is necessary, recognizing that every person has the right to dignified care, as well as the right to provide care. The Chamber of Deputies approved this initiative in 2020, but it is still pending approval from the Senate and the majority of local congresses. Subsequently, it will be necessary to issue corresponding laws and secondary norms to establish the attributions, competencies, and responsibilities of the governments involved in this matter at each institution and level of government. Additionally, it involves granting powers to design the national caregiving policy, which should encompass its sources of financing sources, a component currently absent.

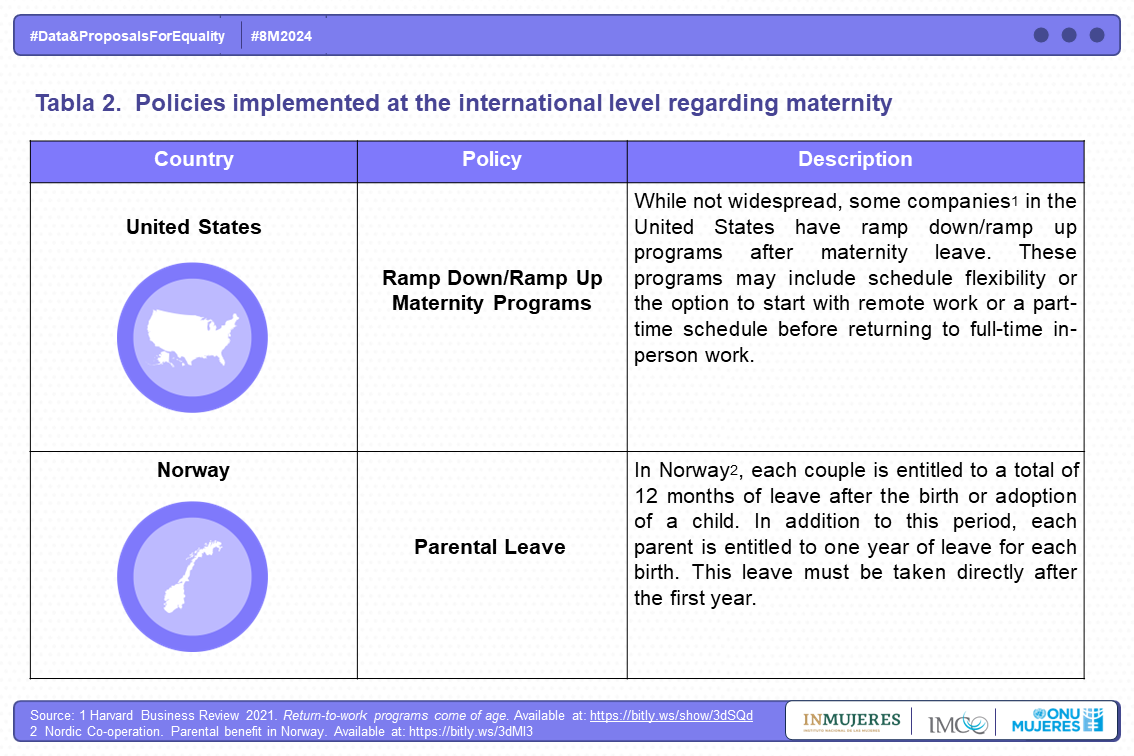

- Implement corporate practices and public policies to facilitate women's return to work after pregnancy. To encourage women to stay on their career paths, several countries and companies have introduced policies promoting gender equality in the labor market by facilitating women's transition back to the workplace after pregnancy.

Key policies include paternity leave or parental leave, the latter often covering longer periods shared between both parents. In the case of Mexico, it’s crucial to adopt paternity leave policies that mirror those of maternity leave. That means that paternity leave permits have the same extension (increasing from 5 to 84 days), are mandatory, with full pay, and funded by social security as with maternity leave.

While not neglecting policies promoting women's inclusion, such as flexible hours, remote or hybrid work, lactation spaces, and phased return programs after maternity leave. In this regard, there are mechanisms like the Mexican Standard NMX-R-025-SCFI-2015 on Labor Equality and Non-Discrimination (NMX 025), promoted by INMUJERES, the Ministry of Labor, and the National Council to Prevent Discrimination. This standard recognizes workplaces that implement policies to promote substantive equality between men and women.

Finally, workplaces seeking to venture into or advance towards greater gender equality can rely on organizations and specialized resources in the field to inform the design and implementation of inclusion policies. Using existing tools can save time and resources, as well as improve results. Some freely accessible options include: UN Women's Women's Empowerment Principles and the UN Global Compact, and the Business Coordinating Council and the UN Global Compact Mexico’s Diversity and Inclusion Implementation Guides: Gender Equality.

Investing in policies that promote progress towards gender equality is essential from a human rights perspective and constitutes a fundamental pillar for the creation of inclusive societies. All sectors possess the capacity to contribute to the construction of more equitable and inclusive societies, as well as the development of competitive economies that benefit everyone.